Block timestamp

openOracle can be run in block.timestamp mode or block.number mode. Base is part of the OP stack which follows the timestamp rules found in the below derivation: https://specs.optimism.io/protocol/derivation.html Some of the important rules from that link are:Chain halt

Applications can ignore reportIds whose settlement timestamp was greater than 60 seconds past eligibility. On OP stack, the L2 timestamp in which user transactions are first included after a restart is still bound below by the L1 block time + max drift. We can have an additional filter in applications of settle block optimality - meaning, if the settle did not come in the optimal block, we ignore the price. In a recent Base outage, empty blocks were posted between the outage timestamp and the restart timestamp, so this increment in block number would be handled by our optimal settle block check and the settled price would not be used.Implied blocks per second

On OP stack chains like Base, the block times and block numbers are relatively well behaved, but for edge case handling applications can calculate an implied blocks per second from the block number and timestamp difference between oracle instance creation and settlement. If this is too far outside the bounds of 0.5 blocks per second (current Base production block rate), the application ignores the settled price. This is not a perfect solution but combined with the OP stack rules it should be useful. Timekeeping is definitely an issue that impacts openOracle. There is a high level of complexity to the timekeeping rules on L2 and it is possible our edge case handling does not cover every edge case. To the extent the edge cases are not predictable, this does not impact oracle performance too much. If they are predictable, because of state hash validation internal oracle participants are not at risk to the same extent external notionals are, like an application relying on the settled price. As with any technology timekeeping will improve.Censorship

Someone can report a bad price, censor any disputes, and then settle the bad price, draining any money that depended on this price. On L2s, we are trusting the sequencer, so in this case we are trusting Base. Base is already trusted for short term inclusion for large defi transactions but if the amount at stake is too high, the sequencer cannot be relied upon. So there is a hard limit on the amount the oracle can secure without better inclusion guarantees. In the case the amount at stake increases to where the sequencer is no longer reliable, we can migrate to the L1. Today, there are 12 second blocks. If we use a 3 minute oracle settlement time, this is 15 block proposers. As long as 1 of n of these proposers includes our transaction, oracle price error is mitigated by dispute inclusion. So we can say crudely an attacker would need to control 15 blocks in a row. An attacker with 30% of stake would get 15 blocks in a row every ~27 years. Even if 3 minute settlement times take longer, all of the math still holds and the oracle works fine. If there is concern about block producer collusion, longer settlement times than that are acceptable. If using the oracle for some linear applications, max slippage and cancels before settlement can be used to reduce settlement times since extractable value is lower. In the not so distant future, we will have FOCIL on the L1. FOCIL gives us inclusion guarantees as long as 1 of 16 of the rotating inclusion committee includes our transaction and the block proposer is not engaging in a block stuffing attack. This may give us the ability to use moderately shorter settlement times on L1, but for super high value transactions it really does not do much unless the settlement time is very long to enable EIP-1559 burns to overwhelm the cartel; however at that point, they fully control the blockchain anyways and can do many more untoward things than attack openOracle. In the case a block proposer decides to censor us and is not engaging in a block stuffing attack, their block is skipped, and the next block number doesn’t change while the timestamp still increments. The oracle does not depend entirely on FOCIL to work, since the only way to pass price error into the oracle is to offer a mispriced swap, and there will be tips for inclusion up to this amount. If we have some initial liquidity L and external linear notional N, set I = L/N, If you calculate 1 / I, you have to bribe that many independent block producers the dispute value to censor. So long enough settlement times are economically unviable for censorship bribery. If you want to impart a grief ratio on the attacker G you can think about (G+1) / I. Parasitic open interest is unstable in high censorship regimes (gets exploited) so it is statistically dead when you as an OI-aware user get a reportId on-chain.Parasitic open interest

Parasitic open interest in openOracle is when an application tries to use an oracle game price without paying for said oracle game. This creates basically two incentives: delay and censorship. The censorship risk does not seem so bad since contrived oracle games exploit the parasitic OI out of existence (possibly via some ePBS-style block space purchase). To the extent parasitic open interest dodges censorship risk, it can actually be a good thing for the parties that paid for the oracle game. For example, in a lending-style liquidation setup, the oracle game can feature protocol fees. For example, 1% of the swap size each round can be charged to disputers then directed to a protocolFeeRecipient address specified at oracle game creation. This address can be a smart contract designed to split the accrued protocol fees between the lender and borrower who paid for the oracle game to start. The delay incentives for liquidation are as follows: P(price X ends past strike Y over settlement time) * payoff of bet > cost to delay oracle where the payoff of bet is the liquidation penalty, Y is the liquidation price, X is the current price, and the cost to delay the oracle is ~ 1% * oracle game size at that round. If the parasitic open interest is very large, the cost to delay is small relatively, but since the initial oracle liquidity was a function of the non-parasitic open interest to begin with (say ~10%), the exponential fees in expectation more than cover for the delay. For example, with a multiplier of 2, the oracle game becomes larger than the paying notional in 4 rounds of delay (10% -> 20% -> 40% -> 80% -> 160%), paying 1% each time split between the original borrower and lender (0.1% -> 0.2% -> 0.4% -> 0.8% -> 1.6% and so on, as % paying notional).Gas fees

Gas fees spiking reduces the profitability of participating in the oracle. If gas fees spike a lot, someone can open a large notional position and report a price that is just wrong enough to make it likely not profitable to dispute because of the gas cost. The advantage on the notional may be much larger than the gas fee paid for the manipulative report. But this works both ways: it is now worth it for their counterparty to correct toward a fair price. So the rare instance of extreme gas fees may be a cost to the traders and counterparties but the cost is smaller than the amount extracted from the notional. We can sidestep the gas fee issues in many cases by having a high floor for the initial report liquidity with some caveats. Initial liquidity should scale proportionately to trade size above that floor. One reason is it links external EV gain in the below manipulation section of the docs to internal oracle losses. We also must compensate the initial reporter for the risk they bear which scales with the amounts. So the up front cost to use the oracle is the initial liquidity compensation which is itself some fraction of the external notional.Block stuffing

Anyone can try a block stuffing attack. If you can increase gas fees enough by spamming high fee transactions, then report a bad price, it isn’t rational to dispute for anyone not economically aligned to the oracle output. This makes it relatively challenging to settle a $1 million dollar notional with something like $100 in the initial report. We will assume there is one gas attacker and their counterparty is completely passive. The attacker can earn the some payoff if they sustain a mispricing for the settlement time. The gas fee per dispute needs to be > R * L, where R is the price error of the report and L is the liquidity in the oracle. So they may need to pay R * L * (G_block / G_dispute) * T, where we have some G_dispute for gas use of a dispute, and G_block for block gas limit, and settlement time of T blocks. Next, on EIP-1559 chains, block stuffing exponentially escalates the base fee +12.5% per block, which is burned. FOCIL helps as well forcing producers to keep blocks full or have their block skipped by consensus. Without FOCIL, block producers can skip an exponential escalation per block they control by submitting empty blocks. The optimal attack is generally to raise the base fee to a bit over the point where it prices out disputers, then alternate blocks in the stuffing attack to keep the base fee stabilized. We will ignore the ramp up period and assume it costs the attacker 0. Block stuffing for the entire period inherits exponential costs and is not really tenable unless the oracle parameters are really bad. So we will say the cost is actually R * L * (G_block / G_dispute) * T / 2. If we assume there is some chance of failure where either the counterparty comes in to blow up the attack, or someone just does it for fun to impart an enormous cost on someone else for a relatively small amount (meaning the attack itself has a really horrible grief ratio to be blown up) by just paying above the gas fee in the non-manipulated alternating block, the profit is decreased. But, we will assume the attack always succeeds. There are a few practical takeaways. First, let’s assume we are on Ethereum L1, where soon there will be a block gas limit of 60 million. Call disputes 250k gas. This is 240 disputes per block you need to price out. For some linear external notional N, you earn R * N and the above cost formula. attack profitability when R * N > R * L * (G_block / G_dispute) * T / 2 ⇒ attack unprofitable when L > 2 * N * G_dispute / (G_block * T) So for a linear notional of $1 million, and we have 15 blocks of settlementTime, you need to pay an initial liquidity of ~ $550. If you want to increase the grief ratio for the attacker, just increase the liquidity, and they blow up linearly. One of the problems with this model is when real gas fees are near the point of pricing out disputes up to some R, the alternating stuffing attack gets cheaper. But this is equivalent to the gas fee problem in general, the liquidity should be high enough so gas fees and even spikes do not impact accuracy more than is tolerable. If we go up to $50k initial liquidity for example, the costs to pay an initial reporter are cheap relative to the $1 million notional, and linear notionals are different from binary like liquidations since the user can choose when they want to trade and customize the parameters per trade. Another issue is the attacker can be a block producer and censor disputes and combine this strategy with alternating stuffing attacks on blocks they don’t control. If the attacker controls some fraction C, we should scale our parameters like initial liquidity / (1-C) or settlementTime / (1-C), or a combination increasing both by some amount. With binary notionals, like liquidations, the required price error is very big. You need to get the oracle to report a price error of the distance from the current price to the liquidation threshold. This should dwarf normal gas fees, and even very high gas fees, for any sensible initial liquidity.Max Slippage

We can imagine using the oracle price to set a swap fulfillment price in some separate swap contract.- User deposits 10 USDC into swap contract, sending a price request to the oracle with some internal swap fee F

- Price request gets an initial report, maybe a dispute or two then is settled at some price

- During the settlement callback, the price is stored in the swap contract and the swap is activated, meaning anyone can come call fulfill

- Fulfill is called, the fulfiller sends an amount of WETH into the contract determined by the stored price and the fulfillment fee L chosen by the swapper, say $9.99 of WETH, and receives 10 USDC back.

Manipulation with a swap fee present

Imagine you are using the oracle to settle a large notional, like a perp open order. You are opening a long and want to manipulate the reported oracle price as low as possible. You can only place the reported price inside the effective fee barrier of the report instance, relative to the true price, or you will instantly be swapped against, which is an optimistic view of dispute network participation but we will stick with it just for this section. This effective fee barrier (called F) will include the internal oracle swap/protocol fees, gas fees, and expected jump loss. Every surviving oracle round (no dispute) is within ±F and every disputed round nets zero, so the manipulator’s cumulative EV is <= F from any game state. We can try to go into what the math looks like to determine how much EV a manipulator can extract even if we know it is bound by F. We will define the ongoing dispute game by three linked states. E_0 is the value from a neutral state, where a manipulator must wait for an opportunity. E_1 is the value from an active state, where a manipulative report is already live. E_2 is the free_move state, which is the initial reporter’s state as well as one branch of the active state. We assume for now the manipulator has 0 expenses and always gets their report on-chain first. Example state paths without conditional survival bias: Trader longs, wants better a opening price, and is using the oracle to settle some external notional. The trader starts the game as an initial reporter (E_2) and chooses a report price R below the true price. This creates a barrier around the true price of (+F-R) / (-F-R). If the true price moves outside of this barrier, the report gets disputed. The true price has three possible paths. One path is it hits neither barrier, in which case the game ends and the manipulator earns some R that is <= F on their external notional. The second path is the price hits the upper barrier +F - R, where there is no move by any active participant other than to have the reported price be the true price. The third path is the price hits the lower barrier -F - R, in which case the manipulator gets a free move. They can place the reported price wherever they would like below the true price, which is equivalent to the initial reporter state. In this third path the game enters back into E_2 and we play again. We say the first, second and third paths happen with some probability P_a, P_b and P_c respectively. Inside the second path of E_2 with an honest reported price, we enter the E_0 game state (neutral). The manipulator’s choice of reported price is constrained by the barriers +F / -F around the true price at 0, since by contract rule you cannot place a price inside the previous report’s fee barrier (we assume for now F = swap fee with every other component of F set to zero). We assume the manipulator waits for the price to hit some Y below 0, at which point they submit a reported price just outside -F relative to the true price when E_0 was entered. So inside E_0, the true price has three possible paths. One path is it hits neither barrier, in which case the game ends and the manipulator earns 0 on their external notional. The second path is the price hits -Y, at which point the manipulator submits a price just outside the lower fee barrier. The third path is the price hits +F, where there is no move by any active participant other than to have the reported price be the true price. Inside the second path of E_0 we enter the E_1 game state (active). The manipulator’s choice of reported price is now constrained by the barrier +Y / (-2F +Y) around the true price at 0. We have three possible paths once inside E_1. One path is the true price hits neither barrier, in which case the game ends and the manipulator earns F-Y on their external notional. The second path is the price hits +Y and we re-enter the E_0 state (neutral). The third path is the price hits -2F + Y and we re-enter the E_2 state (free_move). Below is a more formulaic description of the above example state paths: Paths from E_2: barrier at (+F - R) / (-F - R) P_a: If neither hits -> end game P_b: If +F - R hits -> enter E_0 state P_c: If -F - R hits -> enter E_2 state Paths from E_1: barrier at +Y / (-2F + Y) P(A): If neither hits -> end game P(B): If +Y hits -> enter E_0 state P(C): If -2F + Y hits -> enter E_2 state Paths from E_0: barrier at -Y / + F P(0): If neither hits -> end game P(G): If -Y hits -> enter E_1 state P(H): If +F hits -> enter E_0 state Probability definitions: P(0) = neutral state hitting neither barrier P(G) = neutral state hitting nearer barrier (-Y) P(H) = neutral state hitting farther barrier (+F) P(A) = active state hitting neither barrier P(B) = active state hitting nearer barrier (+Y) P(C) = active state hitting farther barrier (-2F + Y) P_a = free_move state hitting neither barrier P_b = free_move state hitting nearer barrier (F - R_i) P_c = free_move state hitting farther barrier (-F - R_i) Including conditional bias: The surviving price given no dispute is biased depending on its surrounding barriers. One way to think about bias is with the following example: If I told you ETH was $999, and then one week later the only piece of information I gave you was that ETH was below $1000, your best guess for the current price of ETH would be biased much below $999. If I gave you no information one week later, your best guess would be $999. This type of thinking applies to our oracle game. The optimal manipulation strategy does not have symmetrical barriers, meaning the surviving price (no-dispute) is biased away from the true price at time of manipulative report. For example, in the neutral state E_0, if there is no dispute, this means the price did not hit -Y or +F on either side, starting at 0. Since we assume Y is the closer barrier, this biases the price conditional on no dispute closer to the farther barrier. Since the manipulator is opening a long, and wants as low a price as possible, this conditional bias strictly helps them because they got to open a long at a reported price lower than the true price. You can follow the same logic looking at the barriers for E_1 and E_2, and so the no-dispute branches of the active and free_move states have their own specific biases which both hurt the manipulator. We define the three conditional biases as follows: L_0(Y) = Conditional neutral no-dispute price bias (helps manipulator) L_1(Y) = Conditional active no-dispute price bias (hurts manipulator) L_2(R) = Conditional free_move no-dispute price bias (hurts manipulator) Given all of this information, the system is defined by the following three equations:Exponential malaise

Based on the underlying market price action and stylized assumptions about dispute network participation, exponential escalation can shift future costs back into the current oracle accuracy. More specifically, if we assume a disputer is looking at some report that isn’t theirs, and they commit to a defensive dispute then self-dispute every round after that strategy with some proportional cost (like a % burn fee or jump loss), and we have a multiplier M and a per-round settlement (no-dispute) probability Q, then we require Q > 1 − 1/M for the expected total future cost of that “always self-dispute” strategy to stay finite. If actual Q makes this inequality false, the expected future cost can become arbitrarily large, so a rational trader may refuse to dispute unless the mispricing is very big, effectively widening the no-dispute band and worsening oracle accuracy. We can derive this inequality as follows. Assume there is some proportional cost C > 0 to fire a dispute. In the first round, you definitely dispute, so your cost is C. The next round, you might need to dispute with some probability P = 1 - Q, so the expected cost is P * C * M. The round after that is C * (P * M)^2, and so on. The total expected cost is an infinite sum represented byGeneralized oracle games

We can construct a simple English oracle game to show how exponentials may impact generalized oracle games when reporters are pessimistic about participation. Assume there is some oracle question. False has been reported with 5 tokens. The multiplier is 2. So, to dispute this report, you first match the 5 False with 5 True and then put up another 10 on True that anybody can trade against. If nobody disputes for long enough (expiration), the oracle resolves. Someone disputing would need to match your 10 and put up another 20 on False. For marginal questions, we assume a low chance of bubbling up to a network fork like how Amoveo or Augur works. If you win by expiration, you win 5 tokens. If you lose by expiration, this implies your order for 10 was matched, so you lose 15 tokens. You need to have a p(win) > 75% to profit in this market, assuming it does not go all the way to a fork. This somewhat similar to the “dispute and refuse to self dispute” strategy in openOracle. Keep in mind this is a worst-case pessimistic bound - you don’t expect anyone else to necessarily participate on your side given the marginality, meaning there aren’t really paths where your 10 get matched and you still win without a fork. In this simplified example, P(win) > (M + 1) / (M + 2), or it isn’t worth it to participate. The point of this tangent is the following: we shouldn’t expect a simple English oracle game with a 1.01x multiplier to have the same accuracy for marginal reports (like price questions) as that of 1000000x.A stronger form of manipulation

Most of the manipulation analysis we have done revolves around a manipulator reporting wrong prices. A different manipulation strategy would be to always report the true price but dispute and refresh the round timer when the would-be-settled price is not in your favor. Assume you are opening a long and want the settled oracle price lower than the true price. Assume there are 0 swap fees or protocol fees in the oracle game. Also, assume your counterparty is passive and lets you manipulate the oracle. Without manipulation, the reported price would have survived a round with some probability given the dispute barriers. Now, the reported price survives around half that time. We need to figure out what the honest dispute barriers are. We can write a disputer’s EV against any choice of adversarial dispute distance as the below:- dispute_distance is where an honest disputer disputes and earns the absolute difference in token values of the previous report

- adv_dist is where anyone else chooses to dispute the honest disputer’s report. The honest disputer loses the absolute distance in token values in their report, which is at an increased size by the multiplier

- Q(adv_dist) is the probability the price does NOT get to the adv_dist, in either direction

- multiplier is the oracle game multiplier

Quick note on theoretical profit zone

Let’s look at our dispute EV formula again:Back to manipulation

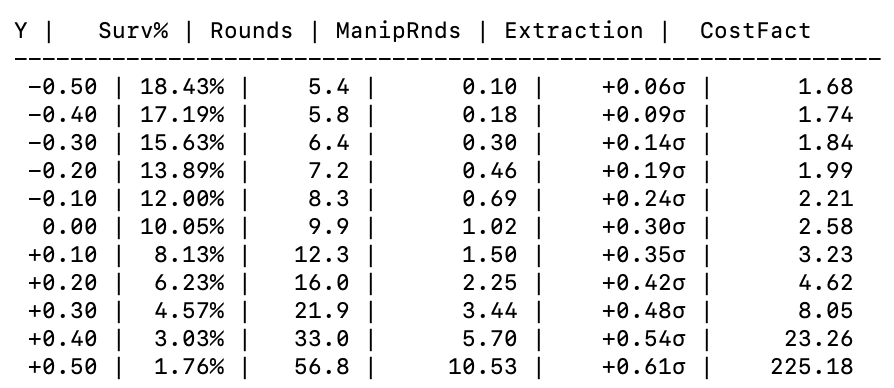

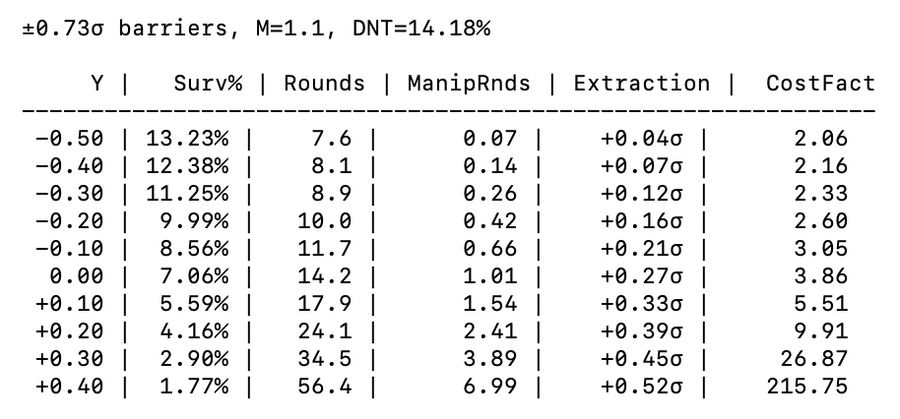

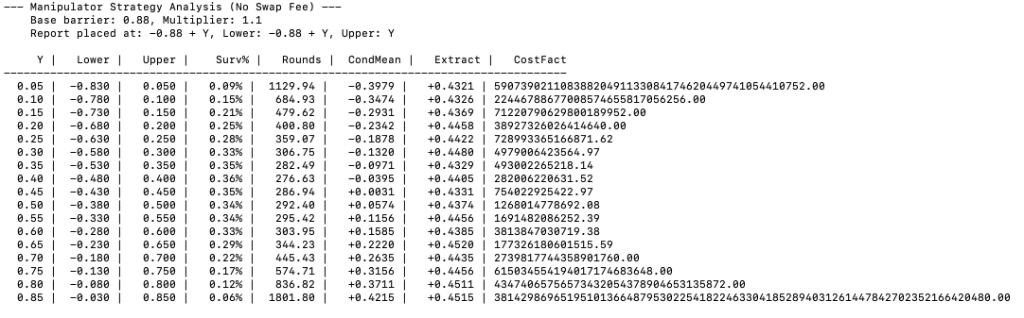

Next, let’s see what a multiplier of 1.3x looks like. We will assume honest dispute barriers of +/- 0.88 st dev, which is somewhat tight but above the theoretical grief-resistant minimum of ~0.832 in a normal distribution. From the original +/- 0.88 barriers, total extraction is ~0.32 and rounds without manipulation is ~3.6. So, starting with 10% initial liquidity, the game would have escalated to ~1.3^3.6 ~= 25% of notional when the manipulator can attempt a dispute. They pay ~ (0.88 * 0.74 * 1.3 * 0.25 - 0.25 * 0.32) ~= 0.13 st dev half the time, and earn 0.32 st dev the other half. It isn’t rational to try again after this (size grows another ~1.3^4.6 times from 25% notional), so the manipulator has ~one 50% chance at extracting 0.32 st dev from the passive counterparty, so they should extract ~ 0.16 st dev on average. Note that the manipulator’s extraction from the passive counterparty is not the same thing as the manipulator’s profits. The passive counterparty doesn’t receive oracle game losses from the manipulator, they just eat the price bias in the oracle game. In terms of Y > 0 strategies, what seems to happen is while the mean extraction increases, the rounds of extraction as a share of rounds that would have settled otherwise decreases. So for example, with Y = 0.2, the survival probability of the oracle is 8.97%, which is ~33% of the ~27% chance the game would have settled otherwise. The cost curve is the same as Y = 0 or worse. So you have ~one attempt at a ~33% chance to extract 0.44 st dev, which is a bit lower expected extraction as Y = 0. At the extremes, like Y = 0.5, oracle survival probability is 1.75% ⇒ 6.5% chance (1.75% / 27%) of extracting 0.61 in the manipulator’s attempt, so it seems like deviating from Y = 0 is worse from an expected profit perspective for the manipulator as long as initial liquidity is not too small. In general, this manipulation style should be modeled more to see what the actual extraction is under an attacker who just prolongs when it’s EV+ and doesn’t otherwise.Viability of committed manipulation strategy

Another thing to consider is the fact that the honest dispute network kind of pushes the game to a knife’s edge relative to the Q > 1 - 1/M violation blow-up, so any strategy that commits to add disputes indefinitely is immediately playing a near-divergent cost game (provided escalationHalt is high enough in oracle game). Honest disputers don’t eat the divergent costs since they are disputing only when it’s worth it to begin with. For example, with a multiplier of 1.1 and assuming dispute barriers of +/- 0.8 (vs theoretical min ~0.7 in normal), we see a ~20% survival rate per round were it only honest disputers. The Q inequality implies ~9.1% is the point at which costs diverge, but even if costs are finite above that they are painfully high until the realized survival rate is much above the floor. For example, let’s add in the manipulator’s prolongation with 10% chance. Now the oracle game survival rate is 10% per round. 10% > 9.1%, but the cost multiple (times whatever proportional cost the oracle game started with) can be represented as:

Manipulation without a swap fee present

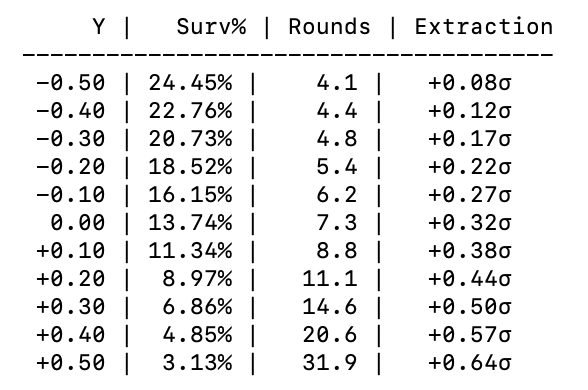

In the “Manipulation” section, we were looking at a manipulation strategy where wrong prices are reported in the oracle. The swap fee by contract rule places restrictions on the allowed price placement, specifically, the new price must be outside the swap fee band around the last report’s price. Assume now we have a 0 swap fee and have a no-dispute band of the multiplier * 0.8 st dev (wider than theoretical minimum). Assuming M = 1.1, this corresponds to dispute barriers of ~ +/- 0.88 st dev. The manipulator was opening a long and trying to get as low a price as possible to settle in the oracle relative to the true price. For this analysis we assume a normal distribution. The game starts with the initial report, where the manipulator places a price some Y above -0.88 st dev. If the true price goes up by just under Y, the manipulator updates their oracle price Y higher, before the honest dispute network can dispute their report profitably. If the true price goes down ~ 0.88 - Y st dev, the manipulator is now breakeven, so they place a new price some Y above -0.88 st dev from the current price at that time. We can model the extractable value as a simple barrier game, with upper barrier at +Y and lower barrier at -0.88 + Y. The reporter earns the spread between the true price and the settled oracle price at time of finalization. For 0.05 increments of choice of Y, we find the below:

Numerical justification for our choices of dispute barriers

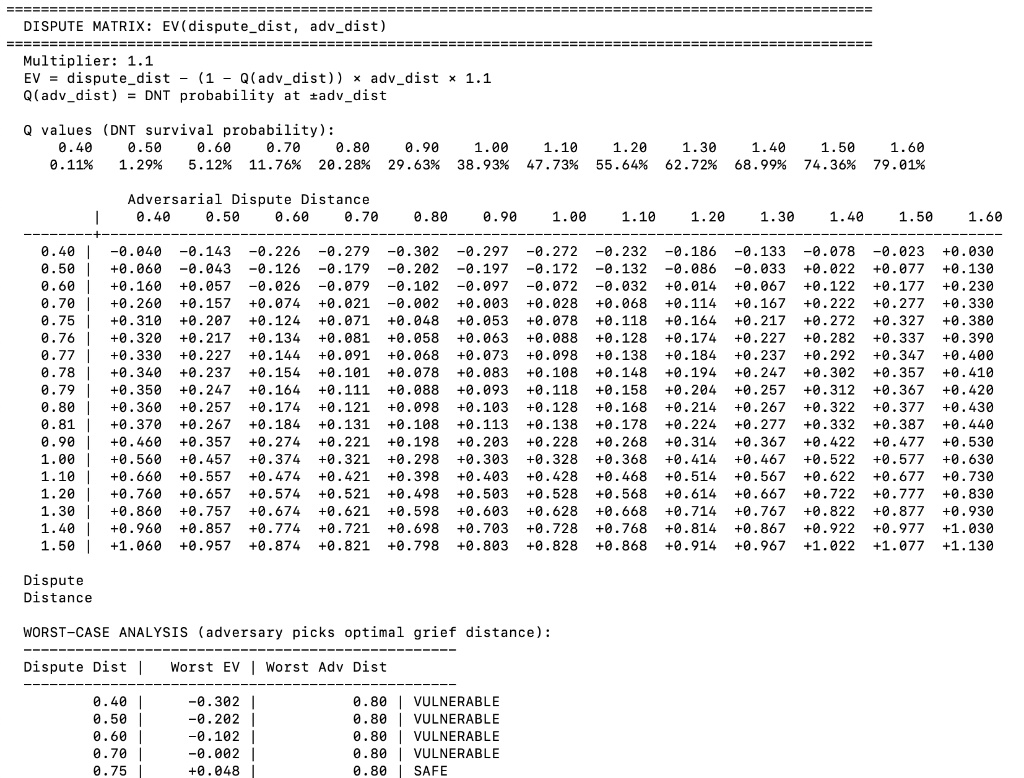

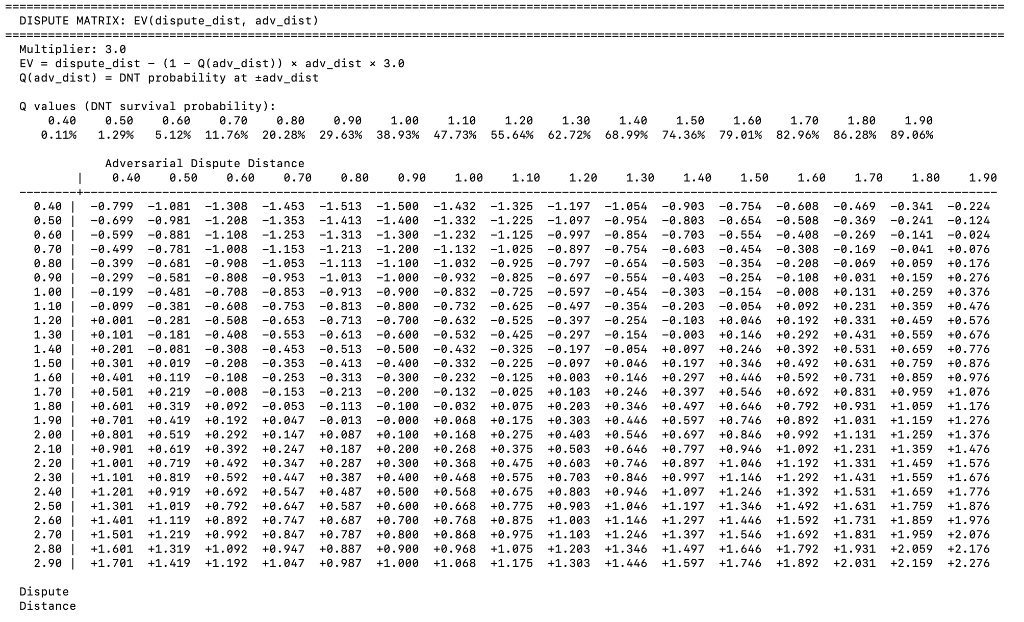

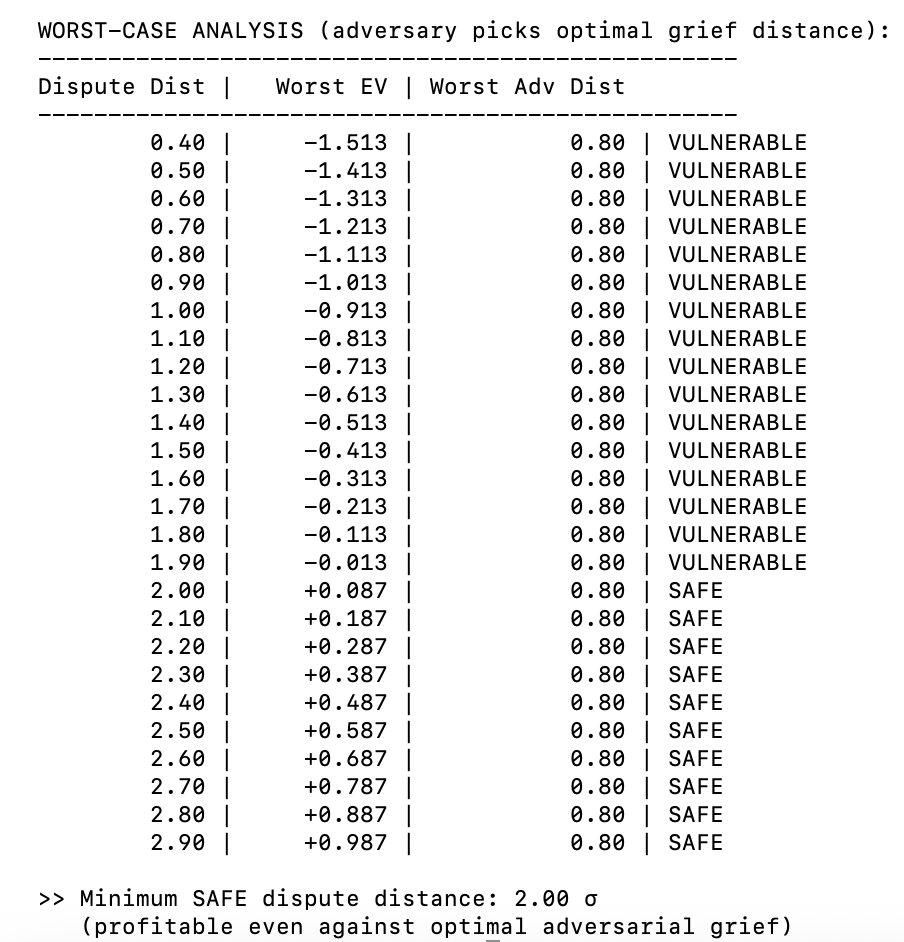

As described in the “stronger form of manipulation section, we can write a disputer’s EV against any choice of adversarial dispute distance as the below:- dispute_distance is where an honest disputer disputes

- adv_dist is where anyone else chooses to dispute the honest disputer’s report

- Q(adv_dist) is the probability the price does NOT get to the adv_dist, in either direction

- multiplier is the oracle game multiplier

Arithmetic dispute barriers versus logarithmic price action

In openOracle, the dispute barriers are ~ 0.65 * volatility * multiplier. Let’s assume for simplicity the volatility * 0.65 is 20%, the multiplier is 1, and we are in some smooth symmetric distribution like a normal. Let’s also assume the honest participants dispute at 20%. From a manipulator’s perspective trying to impart price error to a linear external notional, the no-dispute barriers are +/- 20% (arithmetic bounds), while from the market’s perspective, the chance the price hits +20% is the same as the price hitting -16.6% (log-symmetric bounds). This means the manipulator may have an extra 3.33% of “juice” to capture whenever they finally settle, so they get to extract up to ~3.33/20 ⇒ +0.16F extra. In the real world, when volatility spikes to extremes (say 20% per minute on eth-usd), the distribution is going to be strange, with fat tails, large jumps, lots of cross-venue basis etc, so the extent to which the extra E/(E+1) is extractable may be limited. This environment may increase expected rounds as well despite the extra “arithmetic wedge” in one of the no-dispute barriers.Moral of the story

openOracle price error scales linearly with background market volatility. In the absence of volatility, the oracle cannot drift. The worst-case accuracy bounds (where market volatility dwarfs fixed swap and protocol fees) collapse towards ~ 0.64 * volatility * multiplier. The mean price inside the band remains centered around true price without manipulation. With manipulation, the mean price inside the band can be biased toward the no-dispute band but conditional survival bias on price from optimal manipulator strategy prevents bias-able price error from becoming the entire no-dispute band in expectation. In general, when we think about attacks to bias the mean settled oracle price, there are two categories:- add disputes with correct prices to prolong game if settlement price is against you

- report wrong prices